Related article - Arthur French Poole’s Relationship With Westinghouse & New Haven Clock Company

In the early 1930's, New Haven Westinghouse made a self-starting A/C electric clock with a device called "automatic control." Automatic control is an enhanced power outage indicator. Many A/C electric clocks from that era, such as Telechron, have a window in the dial that turns red if the power is interrupted. When the power is restored, the indicator stays red until manually reset. Thus, a viewer seeing a clock with a red indicator knows that the clock shows the wrong time, but has no idea how far off it is.

With automatic control, if the owner had initially set the automatic control to "1" and set the clock to time, the owner knows this: If the clock is running, it is within one minute of the correct time. Conversely, if the power is on and the clock is not going, the cumulative power outage time is greater than one minute.

Automatic control clocks are operated as follows:

The clock will start running when it is plugged in. If the electric power fails, the automatic control mechanism will start timing the duration of the outage. When the power is restored, the automatic control stops timing and the motor starts running the clock again. Next time the power goes out, the automatic control starts timing again. If the power is off long enough for the automatic control timer to time out, it will lock the wheel carrying the seconds hand, and the clock will not start again when the power is restored.

Two examples of automatic control clocks are shown below. The first has an automatic control lever through the dial, with calibrations from 0 to 3 minutes. The second one has a knob on the back that is rotated to set the automatic control timer. The back of the movement has calibrations from 0 to 3 minutes, but the back of the clock has no calibrations visible to the user!

These clocks are very interesting when they run. The second hand is not a continuous sweep like regular synchronous electric clocks, instead they step in increments of one second. They make a distinct click at each step, and sound louder than the tick of most windup clocks.

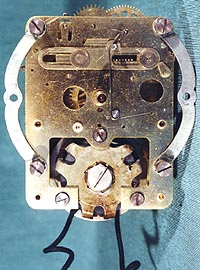

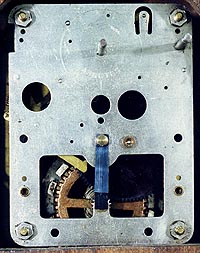

The copper rotor has 36 poles inset into it and rotates at 200 RPM or 3 1/3 revolutions per second. The rotor has a pinion of 15 teeth driving the fiber wheel of 100 teeth, causing the fiber wheel to rotate once every two seconds. The fiber wheel's arbor carries a lantern pinion with only two pins. (On first glance it appears to have some pins missing, but there are no holes for the missing pins). The two pins are diametrically opposite each other. The two-pin pinion drives a ratchet toothed wheel whose arbor carries the second hand. Once a second, a pin in the pinion picks up a tooth in the ratchet wheel and carries it forward. A weighted lever acts as a detent so the wheel moves one tooth at a time, ensuring that the second hand makes one-second jumps.

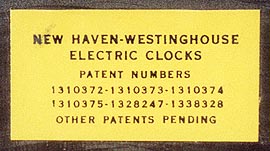

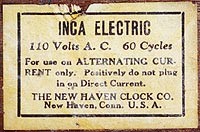

The patents on the label are all issued to Arthur F. Poole and relate to alternating current synchronous time systems.

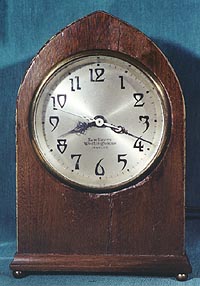

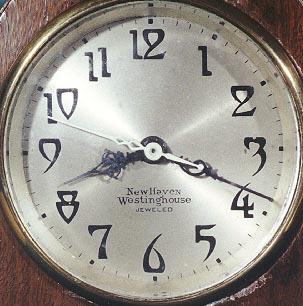

Above: A later New Haven Westinghouse electric with automatic control. Wood case 7 11/16" tall with a 3 1/4" dial. The back is metal. On this clock a knob on the back operates the automatic control. The knob is turned counter clockwise to wind up the automatic control spring. There are no calibrations on the metal back of the case, but the back plate of the movement itself has a circle with calibrations for 1, 2, and 3 minutes (unfortunately this does not show well in the photo). Notice that this movement is nickel plated. This one has a hand set knob on the back, whereas the above example is set by turning the minute hand. (Courtesy of Barry Wheeler).

Note that this model is named Inca.

I want to thank Dr. Snowden Taylor, research chairman of NAWCC , for his article on these clocks in the August, 2000 Bulletin, pp. 523 - 525. Also, thanks to my friend Richard Tjarks for motivating me to study the clocks shown above.